Machine Learning at the Edge and other Advanced Features of Greengrass

We are about to build something really cool. Machine learning inference managed from the cloud but performed at the edge might sound like a sequence of flimsy business colloquialisms and to some extent they might be. In this demonstration, however, we will dive into the actual technical substance behind these terms.

Specifically, we will discuss and apply advanced features of AWS Greengrass, including

- Creating and interacting with a local Shadow

- Shadow synchronisation with the cloud

- Decoupling data generation and application using a Shadow

- Long-lived Lambda functions

- Machine learning resources

- Machine learning inference in the Greengrass Group with a Tensorflow2 model

- The Greengrass service role

The target of the demonstration is to build a small IoT application that predicts whether it is raining or not, given the current temperature, relative humidity, and pressure. The weather data comes from our BME680 air quality sensor, and our Raspberry Pi 3B+ will play the role of gateway device but also runs the code querying the sensor.

We will be utilising expertise from the previous demonstrations of publishing, subscribing, Shadows, and general Greengrass features.

Set Up

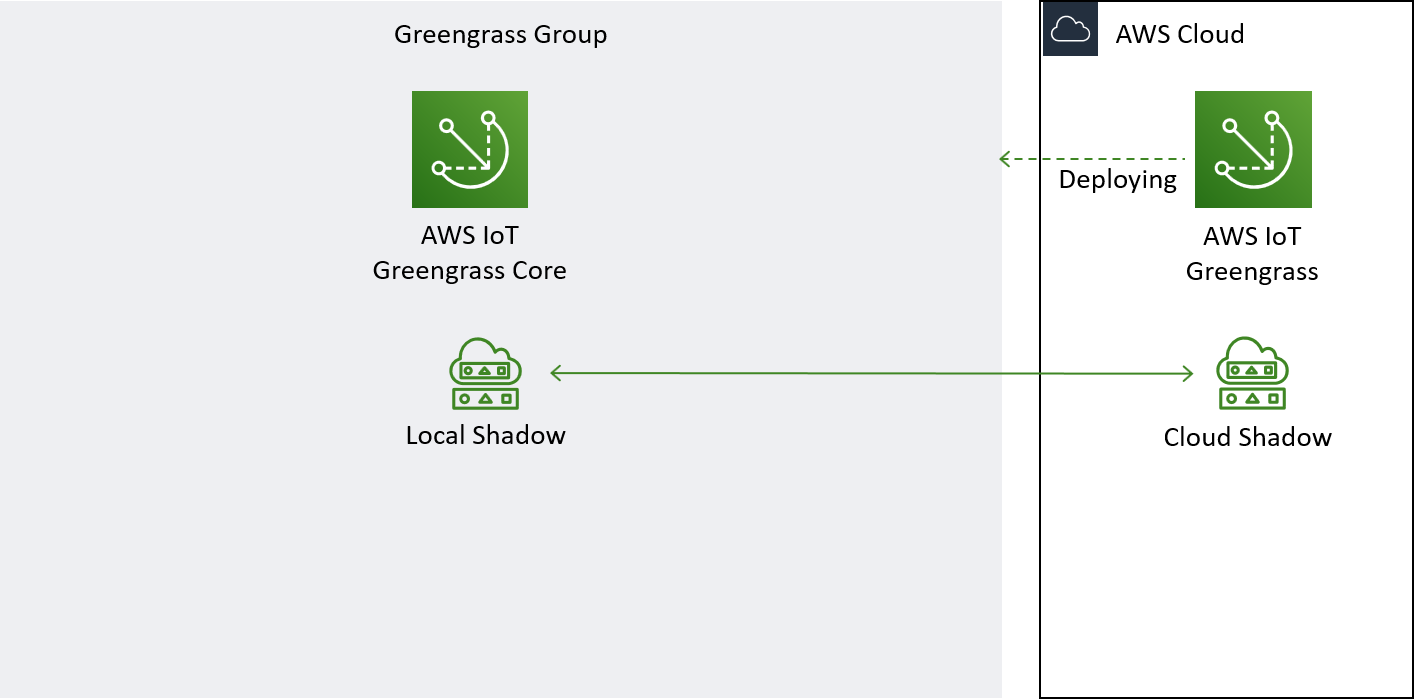

To build the target demonstration, we will walk through three parts. First we will set up a local Shadow within our Greengrass group and use obtained sensor values to contiuously update the Shadow. Then we will enable synchronisation between the local Shadow and a cloud copy of the Shadow. Last, but not least, we will set up inference with a Tensorflow2 machine learning model.

We will not cover installing and setting up Greengrass Group with a device, as this was covered in the general introduction to Greengrass. Be sure to refer to previous demonstrations when in doubt.

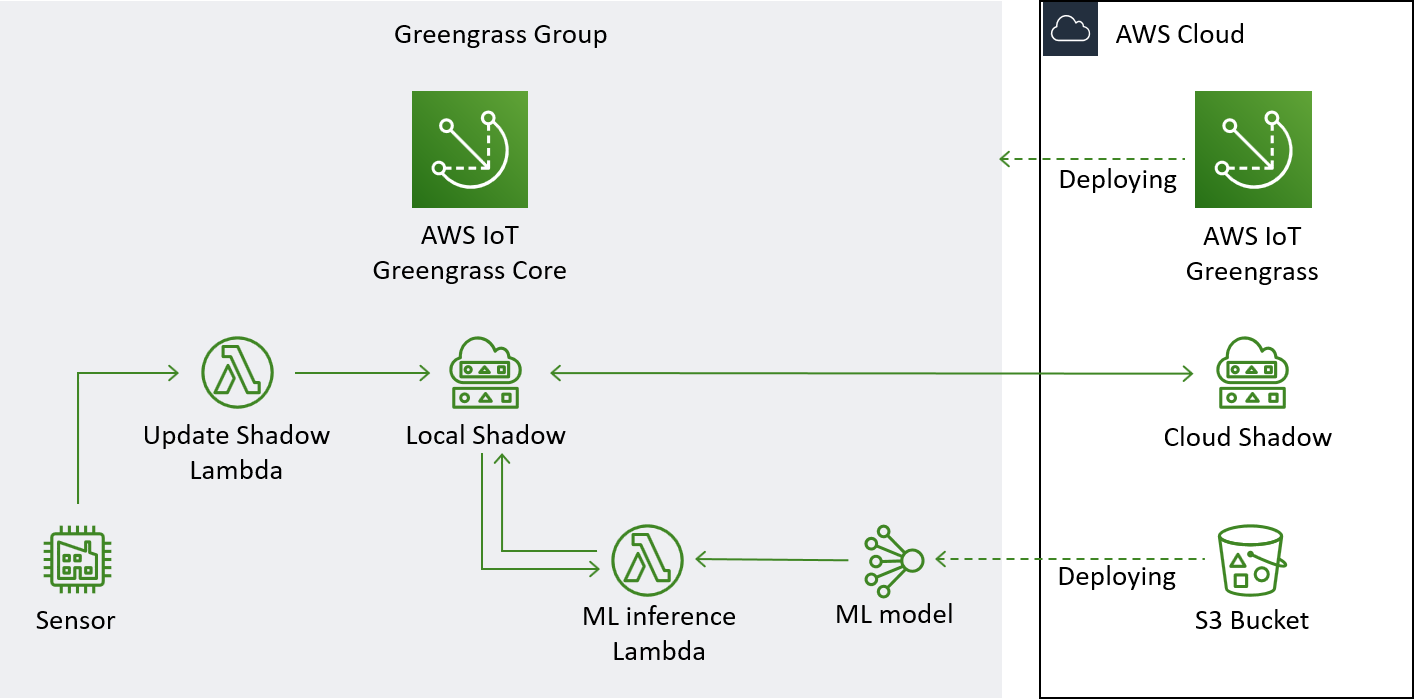

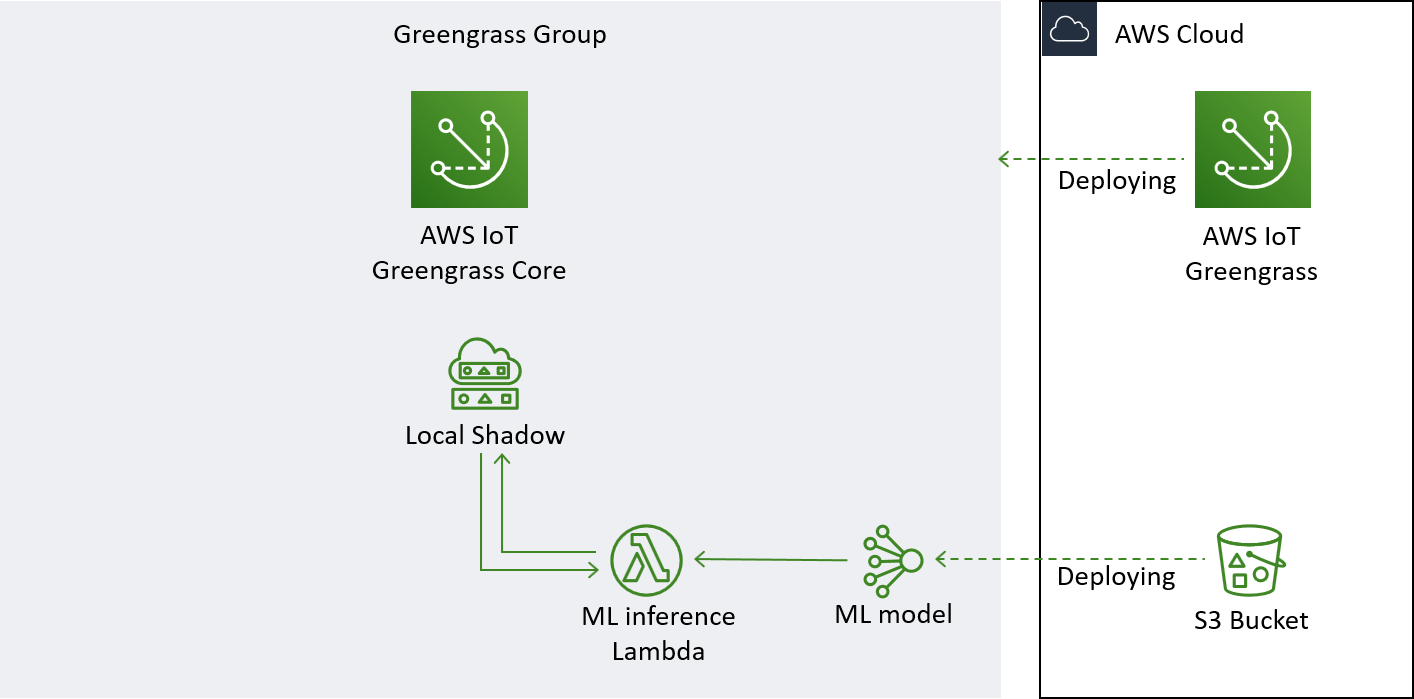

This is the overall architechture of the application we will build in this demonstration.

This is the overall architechture of the application we will build in this demonstration.

Let us get started!

Publish to Local Shadow

In this section, we will set up a local Shadow and build a Lambda function that takes values published by our sensor and updates the Shadow.

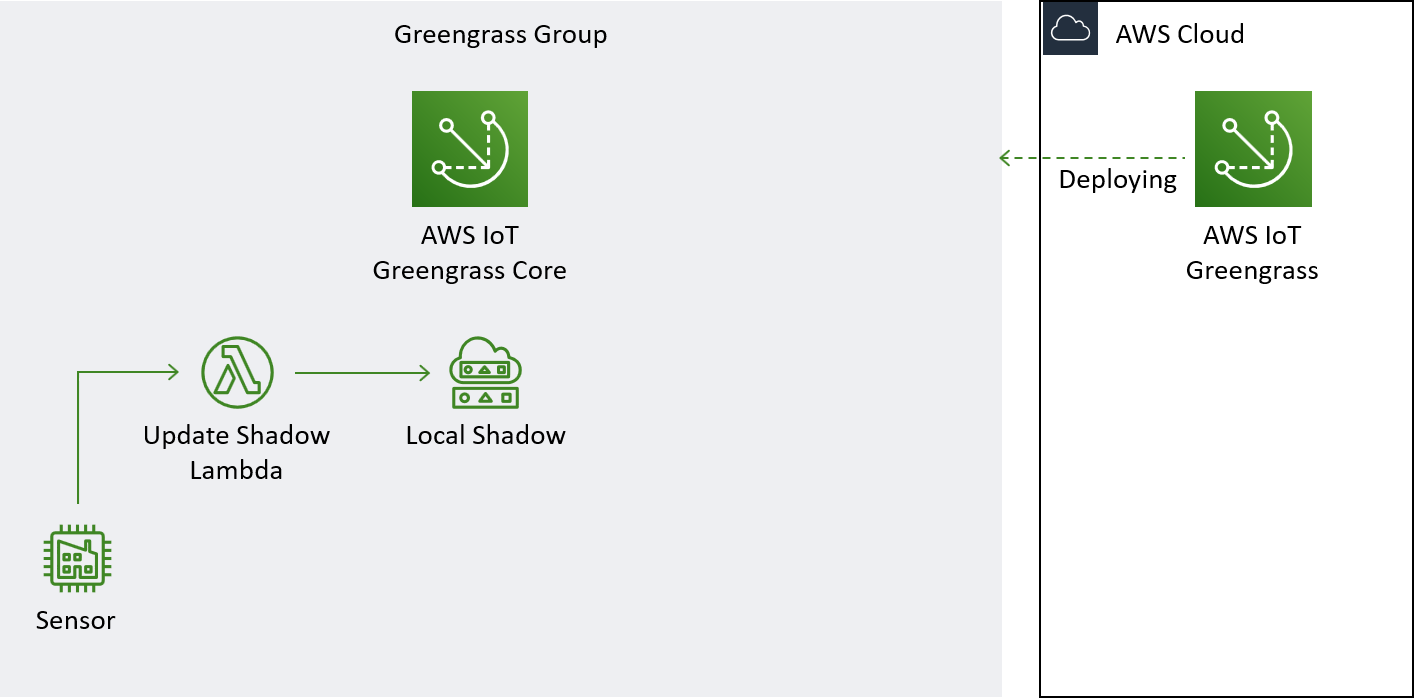

This is the part of the architecture we will build in this section.

Prepare the Thing

We register and add our Thing, the sensor, to our Greengrass group.

We already have a script that connects our Thing and publishes readings to our Greengrass Group on a local topic. There is no need to modify it in any way. We will just leave it running, continuously publishing values to a local topic. I went with the topic bme680/readings but any topic goes.

The Local Shadow Service

Any Thing we include in our Greengrass Group lives only inside the Group and only connects to the cloud when first discovering the Group. This is great for reducing the number of devices connected to the cloud, but it also means that we cannot directly take advantage of the Shadow that is in the cloud.

Fortunately, Greengrass provides a Local Shadow Service inside Greengrass that we can use instead. The local Shadow service works in a very similar way to the Shadow in the cloud. The Shadow document follows the same schema, it is interacted with using the exact same topics, and it can be get, updated, and deleted. The Shadow lives inside the Greengrass Group and is only accessible to entities connected to the group.

For instance, assume we have a Thing called my_sensor and an MQTT client that is connected to our Greengrass Core, we can publish an update to the Shadow of our Thing like this:

from AWSIoTPythonSDK.MQTTLib import AWSIoTMQTTClient

import json

client = AWSIoTMQTTClient('my_sensor')

# Connect the client to Greengrass Core

# ... left out for clarity

# Build an update for the Shadow

message = {}

message["state"] = { "reported" : {"temperature" : 12. } }

# Publish the update to the Shadow

client.publish('$aws/things/my_sensor/shadow/update', json.dumps(message))

The message goes to whichever MQTT server the client is connected to. Since we are connected to Greengrass Core and not AWS IoT, the message never reaches the cloud. So even though the topic is exactly the same as if we were updating the cloud based Shadow, the cloud based Shadow is not updated.

As a matter of fact, the message also does not reach the local Shadow. At least not yet. Since we are working with local topics, we need to set up subscriptions and deploy them to the Group before any messages are relayed.

This is how it could look, but since there is a much easier way, this is not how we will do it.

Republish to Shadow

We will build a Lambda function that will reside in the Greengrass Group. Its purpose is twofold: it will do a bit of transformation on the sensor readings and it will republish the readings as an update to the local Shadow.

Interact with the local Shadow service from a Lambda function

For a Greengrass MQTT client running in a Lambda function that is deployed into a Greengrass Group, interacting with the local Shadow service is very straight forward. We connect and then perform the action we desire:

import greengrasssdk

import json

# Hardcoding the thing name is not a good idea. We will look at an alternative

# in a moment

THING_NAME = 'my_sensor'

# Define and connect the client

client = greengrasssdk.client('iot-data')

# Update the Shadow

update = {"state" : { "reported" : {"value" : 3 }}}

client.update_thing_shadow(thingName=THING_NAME, payload=json.dumps(message))

# Get the Shadow

shadow = client.get_thing_shadow(thingName=THING_NAME)

shadow = json.loads(shadow['payload']) # It takes a bit of unpacking...

# Delete the Shadow

client.delete_thing_shadow(thingName=THING_NAME)

There is no need to deal with callback functions - everthing is taken care of behind the scenes. Furthermore, there is no need to explicitly define the subscriptions in the Greengrass Group for these actions. As long as we use the Greengrass MQTT client, the messages find their way to the local Shadow service, which is just a set of hidden Lambda functions.

We now know everything we need to have our Lambda function perform the transformations we need and update the Shadow. There is just one small aesthetic detail to attend to before we can start building.

Setting environment variables for Lambda functions in Greengrass

In the snippet above, we hard coded the device ID, the Thing name into the Lambda function. This will work just fine, but it does make the Lambda function difficult to reuse. We do, however, have a better option. We can provide Lambda functions running in a Greengrass Group with environment variables. Environment variables are key-value pairs that are specified outside the running script but can be accessed at runtime. If you are already familiar with environment variables for Lambdas running in the cloud, they work in a very similar fashion, but are specified in a different place when used with Greengrass. Let us take it step by step.

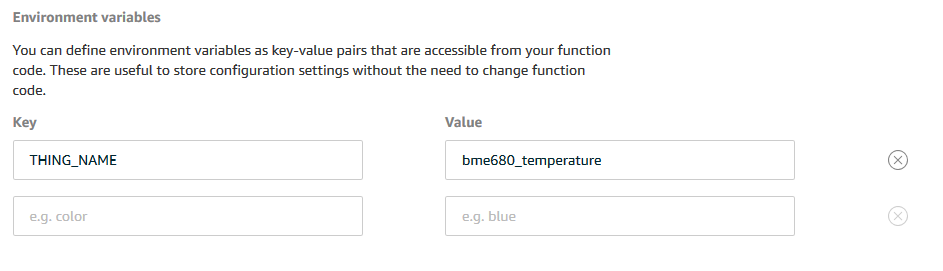

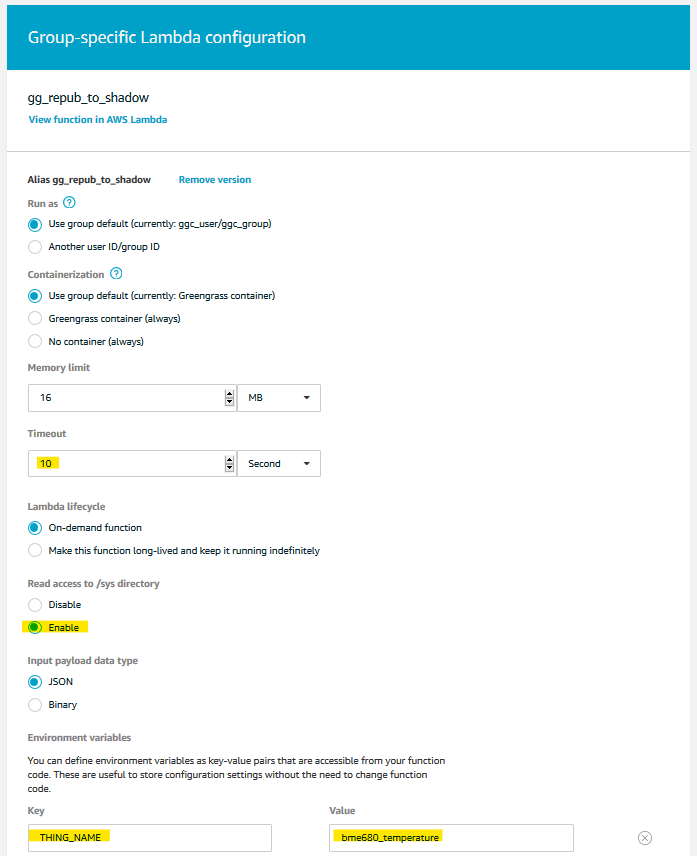

First we will need to decide on a key-value structure. We will go with the key being THING_NAME and the value being the ID of our device.

Then we need to write our Lambda function to take advantage of the environment variable. This is fairly straight forward, in Python:

import os

THING_NAME = os.environ('THING_NAME')

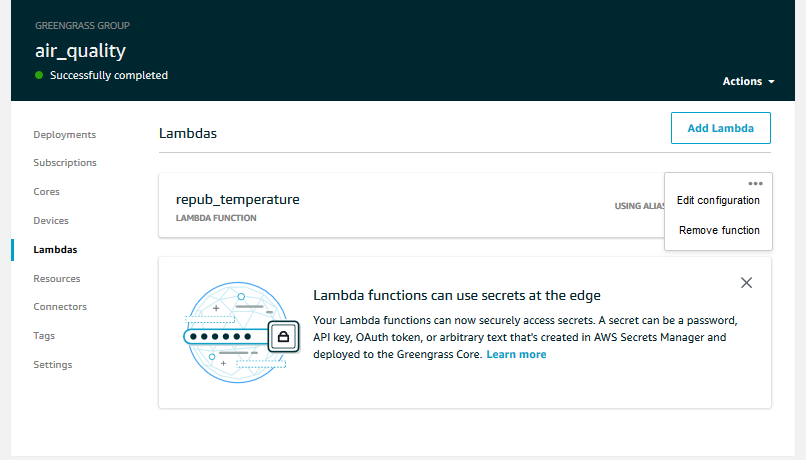

The last step we need is to actually provide the environment variable to the instance of our Lambda function in the Greengrass Group. We do this by locating our Greengrass Group in the console and configure the Lambda in question.

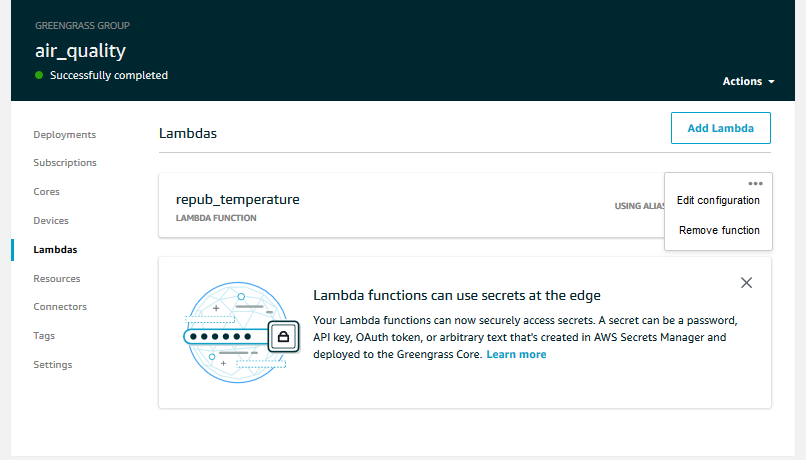

Note that the name of your Greengrass Group and Lambdas may be different

Note that the name of your Greengrass Group and Lambdas may be different

At the bottom of the configuration options, we find a set of fields where we can provide key value pairs, and we just go ahead and provide ours.

Now, when we deploy the Lambda function, the environment variable will be available for use. This means that if we have multiple sensors we we can use the same Lambda Alias to create multiple Lambda functions deployed to the Greengrass Group serving their exact device. Less code and less work for us.

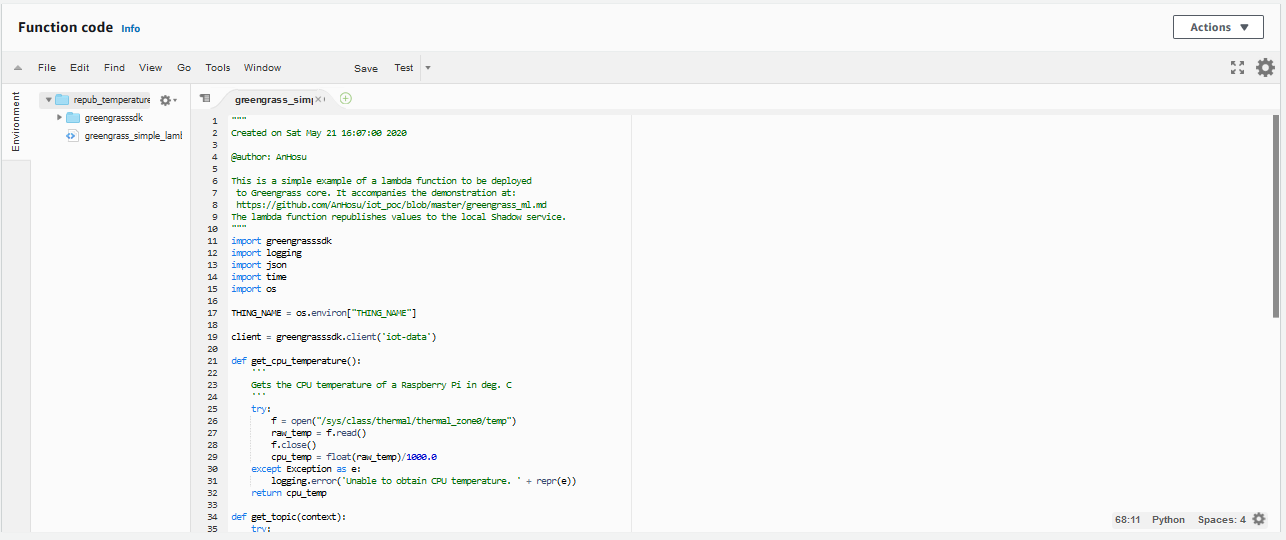

Build the republishing Lambda function

With a bit of additional logging and error handling, we have our Lambda function for transforming and republishing the weather data:

import greengrasssdk

import logging

import json

import time

import os

THING_NAME = os.environ["THING_NAME"]

client = greengrasssdk.client('iot-data')

def get_cpu_temperature():

'''

Gets the CPU temperature of a Raspberry Pi in deg. C

'''

try:

f = open("/sys/class/thermal/thermal_zone0/temp")

raw_temp = f.read()

f.close()

cpu_temp = float(raw_temp)/1000.0

except Exception as e:

logging.error('Unable to obtain CPU temperature. ' + repr(e))

return cpu_temp

def get_topic(context):

try:

topic = context.client_context.custom['subject']

except Exception as e:

logging.error('Unable to read a topic. ' + repr(e))

return topic

def get_temperature(event):

try:

temperature = float(event["temperature"])

except Exception as e:

logging.error('Unable to parse message body. ' + repr(e))

return temperature

def function_handler(event, context):

try:

input_temperature = get_temperature(event)

cpu_temps = []

for _ in range(8):

cpu_temps.append(get_cpu_temperature())

time.sleep(1)

avg_cpu_temp = sum(cpu_temps)/float(len(cpu_temps))

# Compensated temperature

comp_temp = 2*input_temperature - avg_cpu_temp

message = {}

message["state"] = { "reported" : {"temperature" : comp_temp,

"pressure" : event["pressure"],

"humidity" : event["humidity"],

"message" : event["message"]}}

logging.info(event)

logging.info(message)

except Exception as e:

logging.error(e)

client.update_thing_shadow(thingName=THING_NAME, payload=json.dumps(message))

return

The full example script can also be found here. We now need to pack this script in a zip file along with the Greengrass SDK, so we can create a Lambda function. We create the Lambda function and upload the zip file

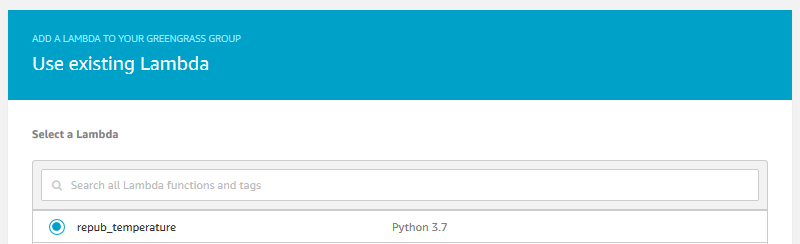

We then create an alias, navigate to the Greengrass console and associate the Lambda function with our Greengrass Group using the alias.

We then cofigure the Lambda function. We need to increase the timeout limit to at least 10 seconds, we need to enable access to /sys so it can get the CPU temperature of the Pi, and we should provide the environment variable as discussed above.

That is it for the Lambda function.

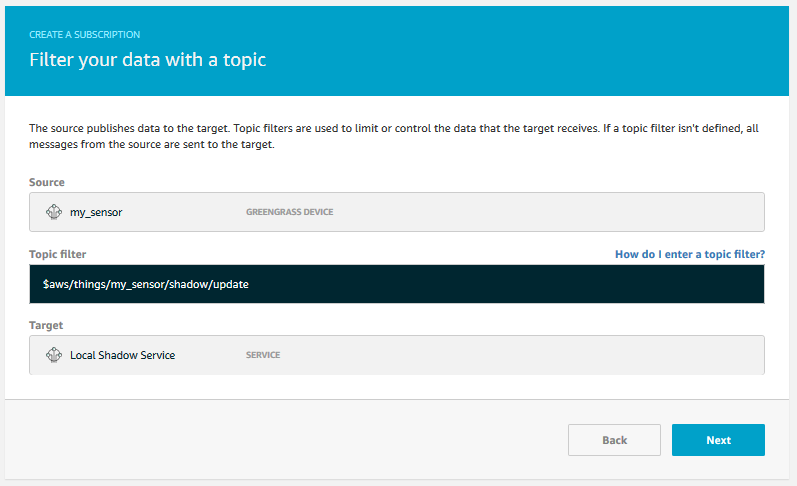

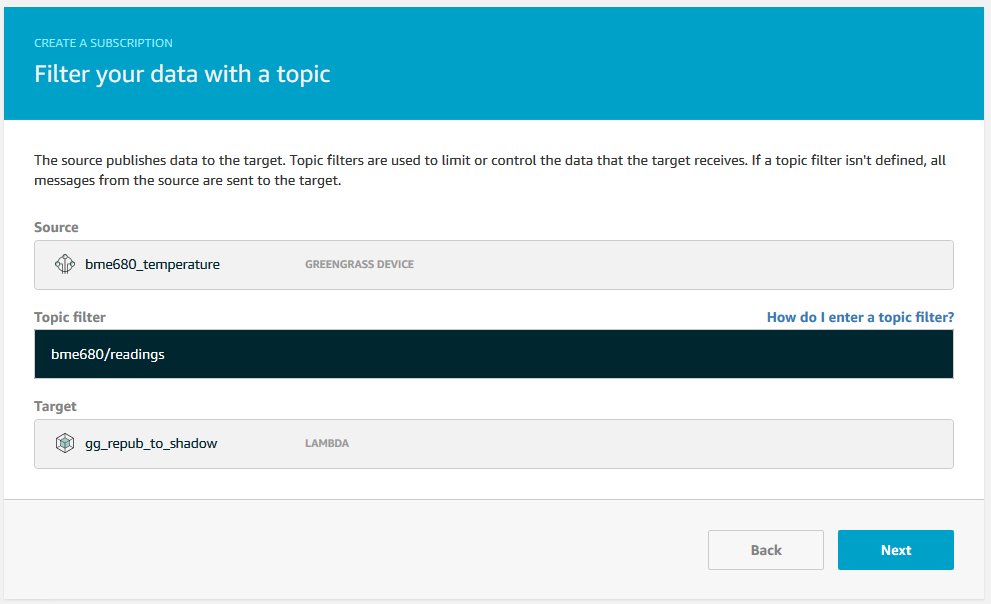

Subscriptions

We only need one subsription, one going from our device to the Lambda we just created.

That is it for the first part. Once we deploy, We have a Thing publishing sensor readings, they are transformed and used to update the local Shadow. Right now there is not much to see though, as we have done nothing to make use of or even visualise the local Shadow. We will get there soon though.

Setup Shadow Synchronisation

In this section, we will set up Shadow synchronisation between the local Shadow and the Shadow of our device in the cloud.

This is the part of the architecture we will build in this section.

This is the part of the architecture we will build in this section.

Synchronising the Shadow just means that the local Shadow service will send regular updates to the cloud based Shadow such that the status quo is reflected there as well. We would usually do this to support an application running in the cloud, but in this case we are doing it mostly for show.

It is important to note that the synchronisation works both ways. Updates that are done to the local Shadow will eventually be reflected in the cloud based Shadow and vice versa. We will not have anything directly updating the cloud Shadow in this case, however.

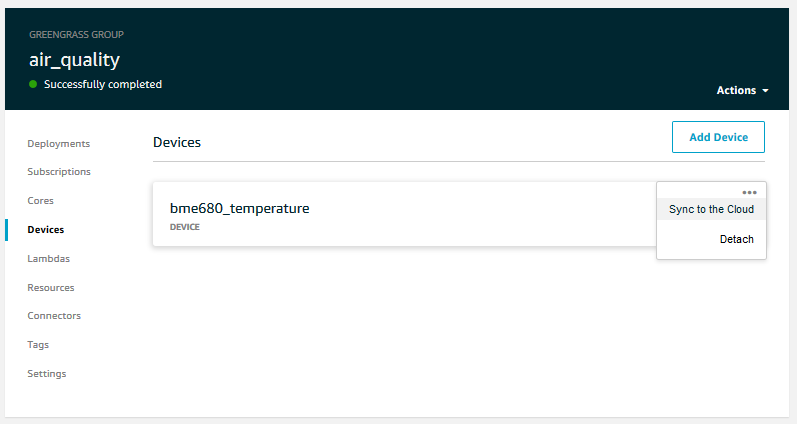

Setting up synchronisation is actually fairly straight forward. We navigate to our Greengrass group and find the Device page. Next to the Device we added earlier it should be saing ‘Local Shadow Only’. All we have to do is to expand the options for that Device by clicking the three dots and selecting Enable Shadow Synchronisation.

Now we deploy the change.

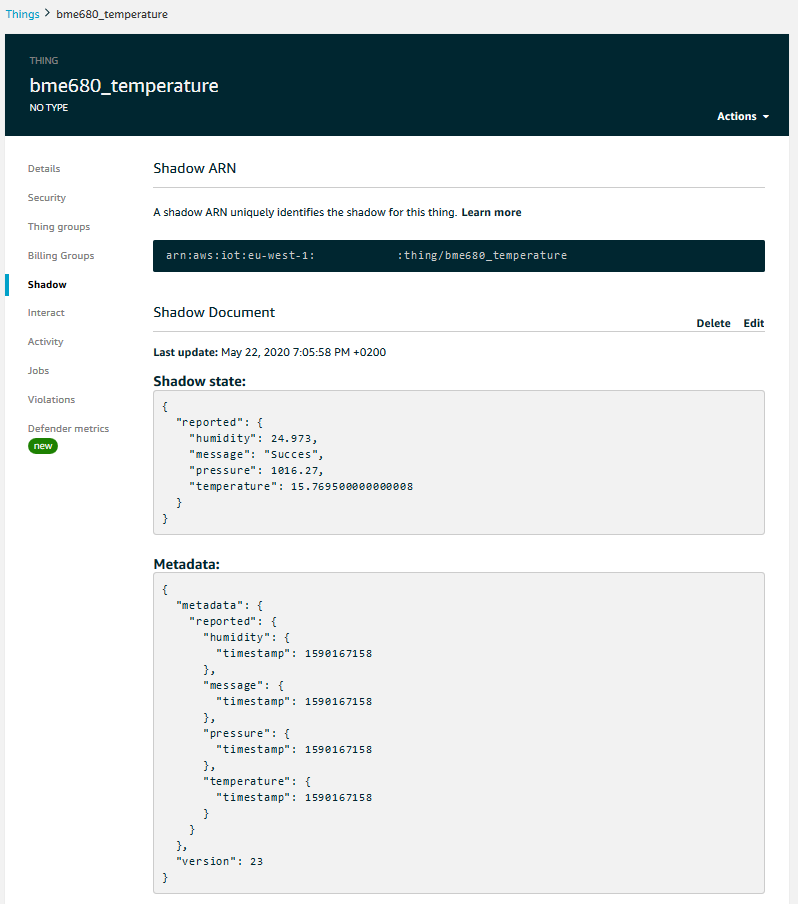

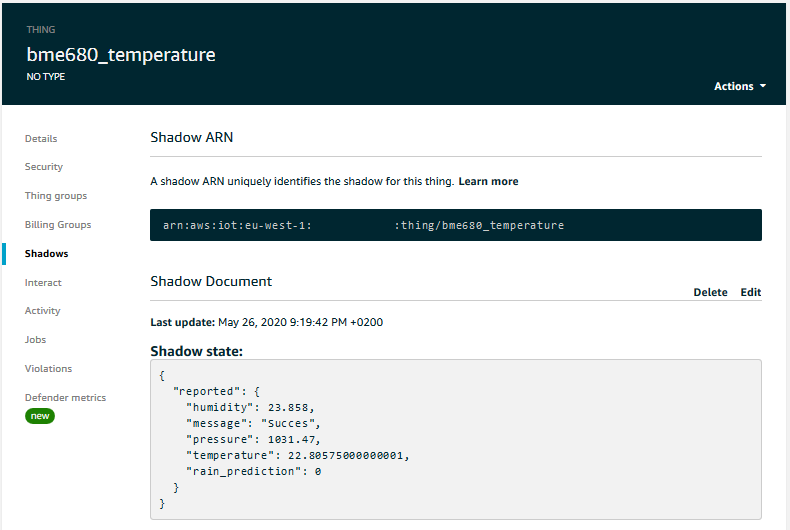

We can test whether it works by navigating to the page of the particular Device and going to its Shadow tab. If everything we did in the previous section works and the Shadow synchronisation works, we should see that the Shadow gets updated.

Machine Learning Inference at the Edge

In this section, we will deploy a machine learning model into the Greengrass group and have it do inference based on the data coming from our Device.

This is the part of the architecture we will build in this section.

This is the part of the architecture we will build in this section.

Specifically, we are going to create a Lambda function that loads a machine learning pipeline consisting of a model that transforms the data into features that are then evaluted in a neural network based model. We will get the data from the local Shadow such that the inference does not rely on live data and inference is effectively decoupled from the data stream.

Prepare the Gateway Device

In order for Greengrass Core to run Lambda functions it needs access to runtimes on the Gateway Device where it runs. When we set up Greengrass Core, we verified that our desired runtime, Python 3.7, was indeed present on the Device, our Pi, and accessible to Greengrass Core. Our approach to the use of additional libraries has been to include them in the Lambda deployment package. For instance, we included the Greengrass SDK with the Lambda function we created above.

Machine learning frameworks like Tensorflow or MXNET are not just libraries but rely on their own runtimes. This means that using such frameworks with Greengrass is slightly more complicated, as we cannot just include the library with the Lambda. Lambdas running in a Greengrass Group can, however, utilise machine learning runtimes if they are installed and available. In fact any library can be used in a Lambda function without including it in the deployment package, as long as it is installed in a shared location on the device.

For this case we are going to use Tensorflow2 to do inference, but Greengrass does support other options.

Install Tensorflow

We will install Tensorflow2 on our Gateway Device, the Pi. How this is done depends very much on the actual device. If you are following along using a Raspberry Pi, and a regular pip install does not work, you might want to check out these unofficial Tensorflow wheels.

The key to making it work, is to install Tensorflow in a shared location (e.g. using sudo pip install) where the Greengrass user, ggc_user, can access it. We can test whether the user can access Tensorflow with the following bash command:

sudo -u ggc_user bash -c 'python3.7 -c "import tensorflow"'

Note, however, that this is no surefire way of knowing whether everything works as expected. Unless you are intimately familiar with your device, it can take a bit of debugging to work. I usually use a Lambda function that just imports Tensorflow and tries something simple like adding two constants and logging the result to test whether the install worked. I deploy the testing Lambda into the Greengrass Group and check the logs for the expected output any unexpected errors.

Our reward for working all this out is that we are able to call Tensorflow2 from within our Lambda function. Now we are ready to do some machine learning.

Manage Machine Learning Resources

To do inference, we are going to need a trained model. A trained should hold everything needed to recreate the function learned from the data during training. This includes the structure of the model, e.g. the layers of a neural network, along with weights, biases, and any other necessary resource. For Tensorflow2, trained models are given in the SavedModel format that can be loaded with a single line of code.

The resources of the trained model then need to be deployed into the Greengrass Group along with the Lambda function that will use it to do inference. Let us give it a try!

A pre-trained model for our case

Building a dataset and training a machine learning model a bit outside our scope for this demonstration and will obviously depend on the choice of ML framework and data science problem, but we are still going to need a model for the sake of example. Recall that we wanted to have a model that given readings of temperature, relative humidity, and atmospheric pressure would predict whether it is raining or not.

I have prepared such a model and described how to save and load a SavedModel with Tensorflow2. It is actually a pipeline of two models closely resembling a real data science workflow. The first model takes in data points, pressure, temperature, and humidity, and standardises them. The second one is a small neural network that takes the standardised features as input and returns a value between 0 and 1, indicating a pseudo-probability of rain.

We will use these two models as examples of doing machine learning inference.

Prepare machine learning resources

In order to include machine learning resources like a Tensorflow SavedModel in a Greengrass deployment, they need to be stored somewhere where Greengrass can access them. Greengrass can access objects in S3 buckets, so this is where we will put our resources.

However, Greengrass is a seperate service and needs permission to access other services. We already had Greengrass access Lambda to fetch deployment packages and that worked smoothly, but we will have to understand why before we can ensure the same for S3.

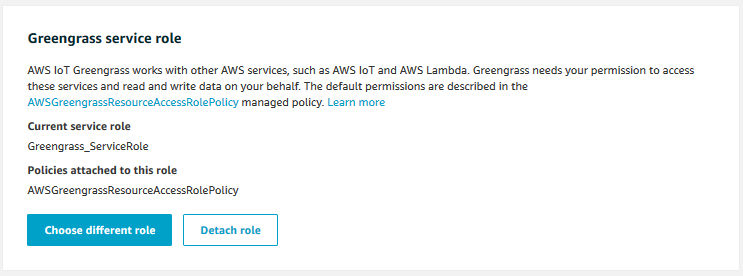

Greengrass has a service role that determines what other services and actions it has permissions to use. The service role can be found in the AWS IoT console under the Settings tab where we also find our custom endpoint. Somewhere in the list of settings is the Greengrass service role.

Per default, the policy attached to Greengrass is the managed policy AWSGreengrassResourceAccessRolePolicy. At the time of writing, the policy is at version 5 and, among other things, it contains these actions:

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Comment": "NOTE: This is not the full or even a valid policy, just a snippet",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "AllowGreengrassToGetLambdaFunctions",

"Action": [

"lambda:GetFunction",

"lambda:GetFunctionConfiguration"

],

"Effect": "Allow",

"Resource": "*"

},

{

"Sid": "AllowGreengrassAccessToS3Objects",

"Action": [

"s3:GetObject"

],

"Effect": "Allow",

"Resource": [

"arn:aws:s3:::*Greengrass*",

"arn:aws:s3:::*GreenGrass*",

"arn:aws:s3:::*greengrass*",

"arn:aws:s3:::*Sagemaker*",

"arn:aws:s3:::*SageMaker*",

"arn:aws:s3:::*sagemaker*"

]

},

{

"Sid": "AllowGreengrassAccessToS3BucketLocation",

"Action": [

"s3:GetBucketLocation"

],

"Effect": "Allow",

"Resource": "*"

}

]

}

We can immediately see why getting Lambda functions worked to smoothly: this default policy allows Greengrass to get any Lambda function, as indicated by the "*" resource identifier. There is also an action allowing Greengrass to get objects from S3. This one however limits the permission to objects that include the string greengrass, sagemaker, or a few variations hereof.

This gives us a choice when storing our machine learning resources: we can either create a new service policy that allows Greengrass to access S3 objects in a format we specify, or we can comply with the constraints of the default policy and name our resources accordingly. The former might not be a good idea because replacing the policy with one we specify means forgoing the benefits of using a managed policy. So we will do the latter and create a bucket with a name containing the string greengrass and put our machine learning resources in there.

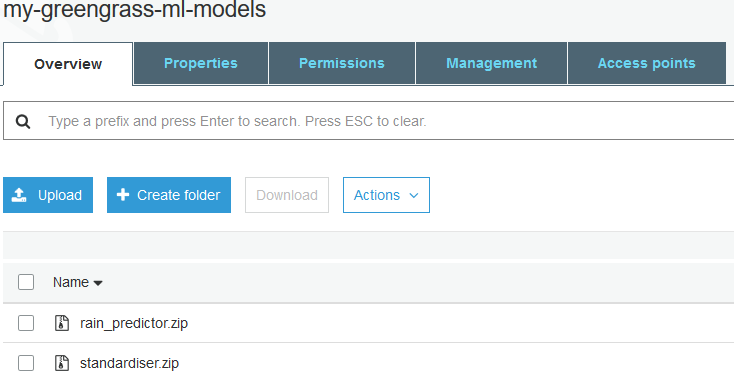

A machine learning resource must be zipped, so we will zip the contents of the two SavedModel folders and put them in the S3 bucket. I have included the zipped models in the project repo as well.

Machine learning resources in an S3 bucket.

Machine learning resources in an S3 bucket.

Greengrass will unzip the contents when deploying into the Group. Now we just need to tell Greengrass where the resources are and where to put them.

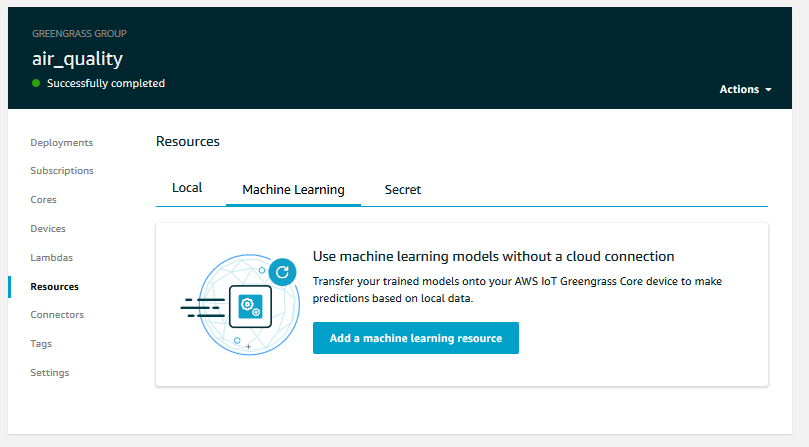

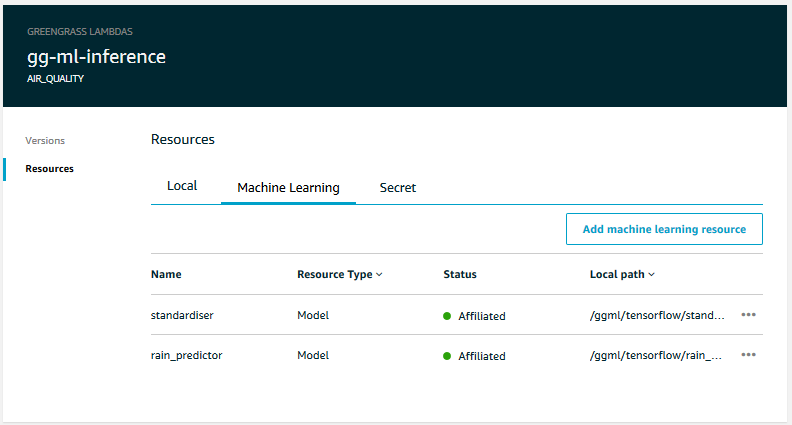

Create machine learning resources in Greengrass

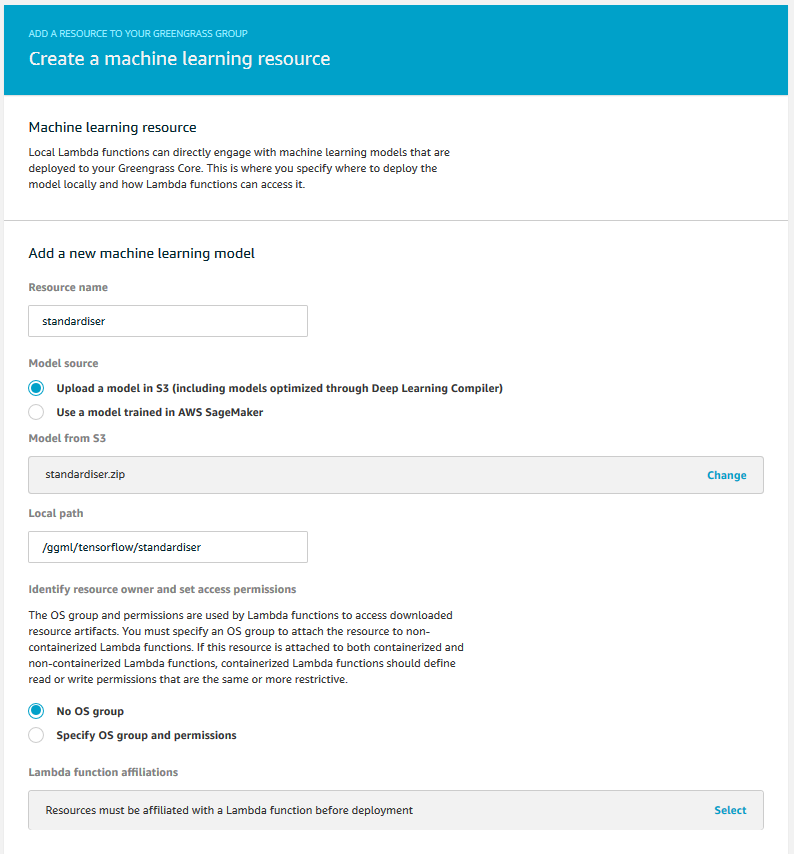

Now we are ready to configure machine learning resources in Greengrass. To do so, we locate our Greengrass Group in the console and navigate to the Resources page and the Machine Learning tab. We click the ‘Add machine learning resource’ button.

Let us start by creating a resource for the standardiser model. First we will give the resouce a name. I went for standardiser but anything goes. Next, we will need to point to the resource in our S3 bucket. Under ‘Model source’ we choose ‘Upload a model in S3’, select the bucket we just created, and then select the zipped standardiser model. Finally, we will specify a local path on which to keep the unzipped model. Greengrass will create this path on our Core Device and it will be available to the Lambda functions that this machine learning resource is attached to. Any path works, but remember it, as we will need it when we create the inference Lambda function. I went with /ggml/tensorflow/standardiser.

We have not created the Lambda function yet, so we cannot attach the resource just yet. We Will have a chance to do so later, though. Click Save to create the resource.

This created the ML resource for the standardiser. We will need to repeat the process to create a resource for the neural network model, which I named rain_predictor and stored at /ggml/tensorflow/rain_predictor.

Inference Lambda

We are almost done building the architecture of our demonstration. We just need the final and arguably most interesting piece; the Lambda function that does inference.

The function we are about to build will load the ML pipeline, fetch the latest data from the local shadow, perform the inference, and publish the result back to the local shadow. In pseudocode, we will do something like this:

connect to Greengrass crore

load standardiser

load neural network model

while true:

fetch data from the local shadow

standardise the data

evaluate features in the model

determine prediction based on threshold

publish reult to local shadow

wait a little while

Connect and get readings

We already know how to interact with the local shadow. We will use an environment variable to supply the name of our Thing

import greengrasssdk

import os

THING_NAME = os.environ["THING_NAME"]

client = greengrasssdk.client('iot-data')

We can then get the latest data from the local shadow

thing_shadow = client.get_thing_shadow(thingName=THING_NAME)

The shadow requires a bit of unpacking

import logging

import json

def parse_shadow(thing_shadow):

try:

reported = thing_shadow["state"]["reported"]

readings = [reported["pressure"],

reported["temperature"],

reported["humidity"]]

except Exception as e:

logging.error("Failed to parse thing_shadow: " + repr(e))

return [readings]

readings = parse_shadow(thing_shadow=json.loads(thing_shadow["payload"]))

Load model

In order to load our models, we need the paths that we defined for the corresponding ML resources:

import tensorflow as tf

STANDARDISER_PATH = "/ggml/tensorflow/standardiser"

MODEL_PATH = "/ggml/tensorflow/rain_predictor"

# Load the model that standardises readings

loaded_standardiser = tf.saved_model.load(STANDARDISER_PATH)

inference_standardiser = loaded_standardiser.signatures["serving_default"]

# Load the model that predicts rain

loaded_predictor = tf.saved_model.load(MODEL_PATH)

inference_predictor = loaded_predictor.signatures["serving_default"]

Inference

Given the data and the models, we can go ahead and implement ML inference and publish the results

CLASSIFICATION_THRESHOLD = 0.5

# Standardise readings to create model features

feature_tensor = inference_standardiser(tf.constant(readings))['x_prime']

logging.info(feature_tensor)

# Perform prediction

raw_prediction = inference_predictor(feature_tensor)['y'].numpy()

# Evaluate prediction

prediction = (raw_prediction >= CLASSIFICATION_THRESHOLD).astype(int).tolist()[0][0]

# Publish result to the local shadow

shadow_update["state"] = {"reported" : { "rain_prediction" : prediction } }

Create Lambda deployment package

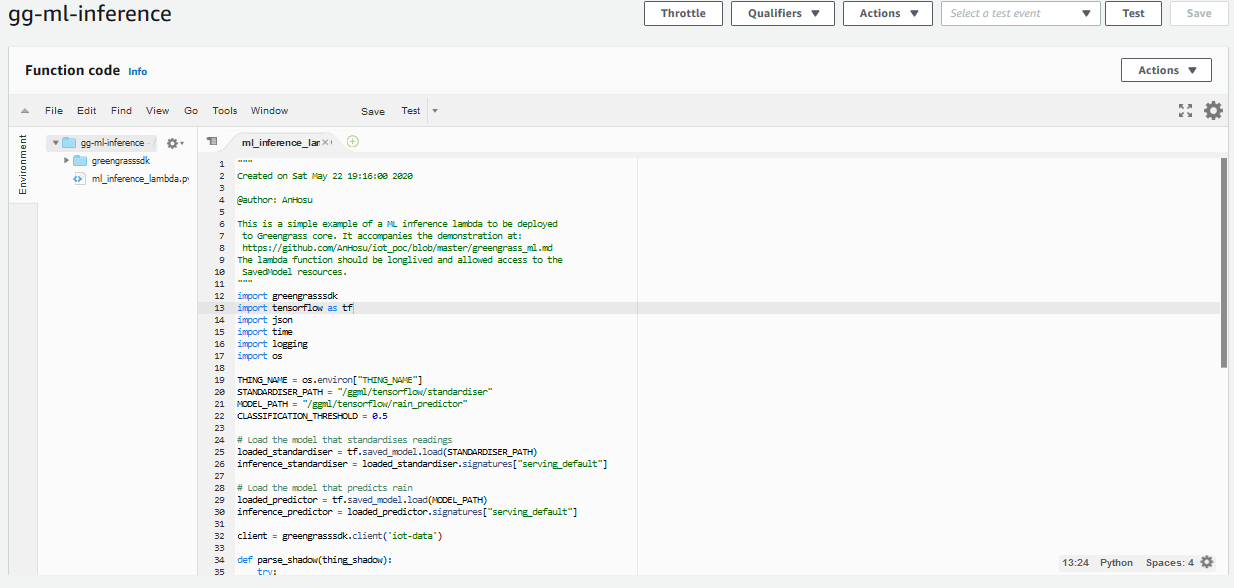

With a bit of additional error handling and logging, we have everythin we need for our inference Lambda

import greengrasssdk

import tensorflow as tf

import json

import time

import logging

import os

THING_NAME = os.environ["THING_NAME"]

STANDARDISER_PATH = "/ggml/tensorflow/standardiser"

MODEL_PATH = "/ggml/tensorflow/rain_predictor"

CLASSIFICATION_THRESHOLD = 0.5

# Load the model that standardises readings

loaded_standardiser = tf.saved_model.load(STANDARDISER_PATH)

inference_standardiser = loaded_standardiser.signatures["serving_default"]

# Load the model that predicts rain

loaded_predictor = tf.saved_model.load(MODEL_PATH)

inference_predictor = loaded_predictor.signatures["serving_default"]

client = greengrasssdk.client('iot-data')

def parse_shadow(thing_shadow):

try:

reported = thing_shadow["state"]["reported"]

readings = [reported["pressure"],

reported["temperature"],

reported["humidity"]]

except Exception as e:

logging.error("Failed to parse thing_shadow: " + repr(e))

return [readings] # Note predictor expects shape (observations X num_features)

shadow_update = {}

while True:

try:

# Get readings from local Shadow

thing_shadow = client.get_thing_shadow(thingName=THING_NAME)

# Put readings in a list in the right order

readings = parse_shadow(thing_shadow=json.loads(thing_shadow["payload"]))

# Standardise readings to create model features

feature_tensor = inference_standardiser(tf.constant(readings))['x_prime']

logging.info(feature_tensor)

# Perform prediction

raw_prediction = inference_predictor(feature_tensor)['y'].numpy()

# Evaluate prediction

prediction = (raw_prediction >= CLASSIFICATION_THRESHOLD).astype(int).tolist()[0][0]

# Publish result to the local shadow

shadow_update["state"] = {"reported" : { "rain_prediction" : prediction } }

except Exception as e:

logging.error("Failed to do prediction: " + repr(e))

client.update_thing_shadow(thingName=THING_NAME, payload=json.dumps(shadow_update))

time.sleep(10) # Repeat every 10s

# The function handler here will not be called. Our Lambda function

# should be long running and stay in the infinite loop above.

def function_handler(event, context):

pass

The script can also be found here.

We zip this script along with the Greengrass SDK and create a deployment package.

We then create an alias, go to the Greengrass console, and add the Lambda function to our Group.

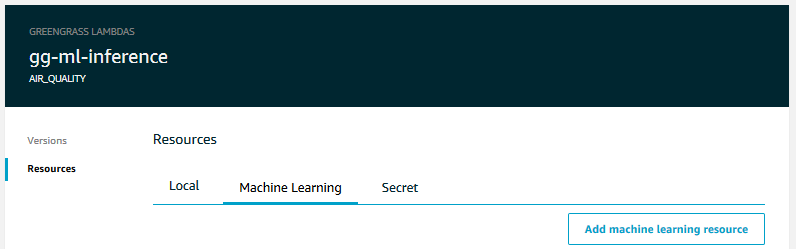

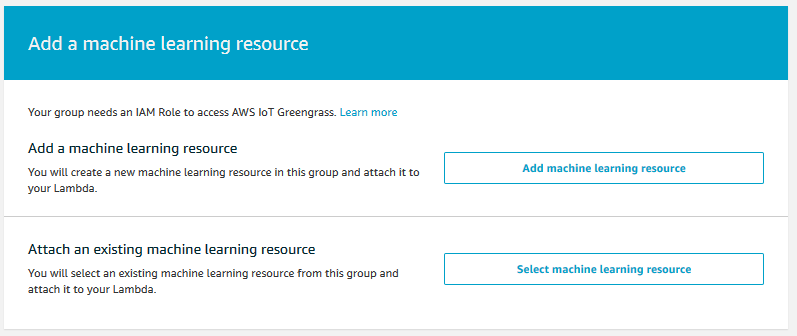

Attach machine learning resources

Now we can finally attach the machine learning resources to our Lambda function. We navigate to our Greengrass Group and under the Lambdas tab select our inference Lambda. Under the Resources tab, we select the option to ‘Add machine learning resource’

Since we have already created the resources, we select the option to ‘Attach an existing machine learning resource’.

We select either of the two resources, click ‘Save’, and repeat the the process for the other resource.

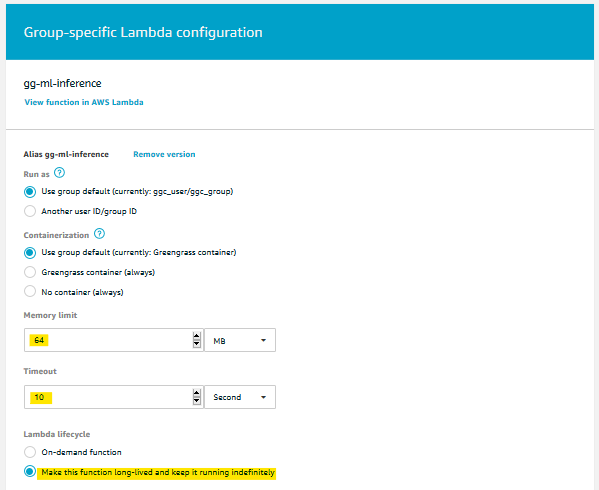

Configure the Lambda

Our inference Lambda is almost done, we just need to configure it properly. All Lambda functions we have used with Greengrass so far have been on-demand functions that were spawned in response to an MQTT message. This inference Lambda is a bit different. Instead of waiting to process an input on-demand, we want this function run on on a fixed schedule, which we implemented by having the inference code repeat every 10 seconds. In fact, we do not want the Lambda to respnd to any events at all and consequently left the function_handler empty.

# The function handler here will not be called. Our Lambda function

# should be long lived and stay in the infinite loop above.

def function_handler(event, context):

pass

Once the Lambda is deployed to our Greengrass Group, we just want it to run forever in the infinite loop we created. This is called a long-lived Lambda, and we can choose this option on the configuration page of the Lambda in the Greengrass Group. While we are in there, we will also give the Lambda a longer timeout and some more memory. Our ML model is small, but ML models are often large and require much more memory.

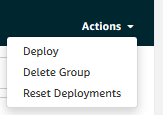

Deploy and Verify

That is it; everything is in place for doing machine learning inference at the edge.

First let us ensure that Greengrass is running using:

ps aux | grep -E 'greengrass.*daemon'

Then we deploy everything we have created.

Finally, we make sure that the Thing is online and is publishing values from our sensor.

Now, if everything works is right, we should be doing inference at the edge. We should be predicting whether it is raining or not and publishing the result to the local Shadow. Since the local Shadow is being synchronised with the cloud based Shadow, we should be able to see the predictions if we go to the Shadow page of our Thing.

And there it is! It is a sunny day, so the prediction was right this time, but do not expect it to be very precise. Instead bask in the glory of accomplishment and enjoy the fact that you now know how to manage machine learning models in the cloud and do inference on the edge. Congratulations!

In Production

While we have done much there are still many more things to consider when using Greengrass for machine learning workloads in production. Here is a short discussion of some of these considerations along with a few points and tricks that did not fit in the demonstration.

Logging in Greengrass

Greengrass features pretty extensive logging. Logs pertaining to the Lambda functions running in the Greengrass Group can be particularly useful during development as well as production. The Logs are stored on our gateway device on a path that depends on user ID and AWS region. It is fairly straightforward to add log entries from a Python Lambda function.

import logging

# Log an error

logging.error("Hypothetical error")

# Log some information

logging.info("My value is 2")

All sorts of things can and will go wrong when developing, and so a very useful Python design pattern to use in Lambda functions is the try and except with logging.

a = 4

try:

# Do whatever we are trying to do

a += 1

except Exception as e:

# Log the variables at this time

logging.info("a is {0}".format(a))

# Log the exception along with a description of what was supposed to happen

logging.error("Failed to do the thing I wanted: " + repr(e))

Indeed we did apply this design pattern in the examples for this demonstration so, when something is not working as expected, check the logs.

CI/CD

We implemented many different parts in this demonstration, and repeating this manual process is obviously not feasible for real IoTs with hundreds of devices. CloudFormation templates will work wonders for the cloud side of things. But, even if we are using AWS IoT services, an IoT very much is a hybrid setup. We still need to install and manage the software running on and near gateway devices and sensors. All in all this sets quite high demands for our CI/CD pipelines.

For data science projects, however, publishing models to an S3 bucket and inference code to Lambda are relatively trivial tasks, so at least this part of CI/CD can be much easier with Greengrass.

Cost

We have not specifically addressed the subject of cost during this or the previous demonstrations. To be clear, everything we have done in this demonstration and the previous ones should be well within the Free Tier, assuming eligibility and that things are not left running indefinitely. But what about larger IoTs?

Pricing for AWS IoT and AWS Greengrass is fairly transparent and we can connect a lot of devices and send a lot of messages before raking up a bill of any significant size. Indeed, if we did not do Shadow synchronisation, we could copy the architecture of this demonstration, scaling it to hundreds of manufacturing lines, and it would cost us less than $2 per gateway device per year. So does that mean that doing IoT is super cheap? No, it just means that the bill lies elsewhere.

From a cloud point of view, sending messages to AWS IoT does not do much. The messages are not kept or processed in any way, unless we do so actively. Herein lies a hidden cost: We are going to need more services like Kinesis, SQS, SNS, S3, or DynamoDB before we can start using our data. In particular, processing using cloud compute can be expensive. One of the key reasons for using Greengrass was to lower processing costs by using compute available at the edge. Yet, this means we have to have an edge.

So, from an edge point of view, we could argue that the whole cloud thing is just an add on to the costs that we already have in building and maintaining servers and networks around whatever process we building an IoT for.

The point is that, even though AWS IoT prices are reasonable and transparent, these are only a small part of the total cost and business case for an IoT. Depending on our intended applications and the tools available locally, it might or might not make sense to involve the cloud. That being said, IoT can be a cheap and fun way to get started with the cloud.